by Lucy

on March 26, 2012

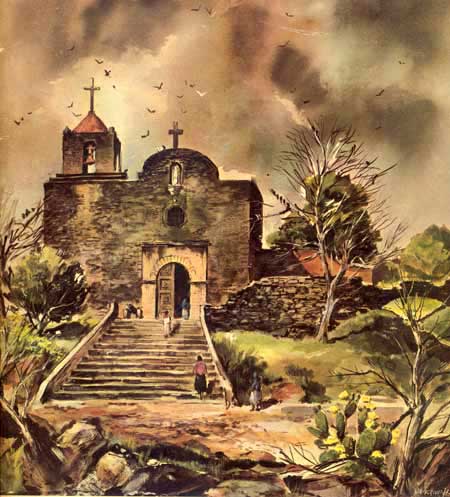

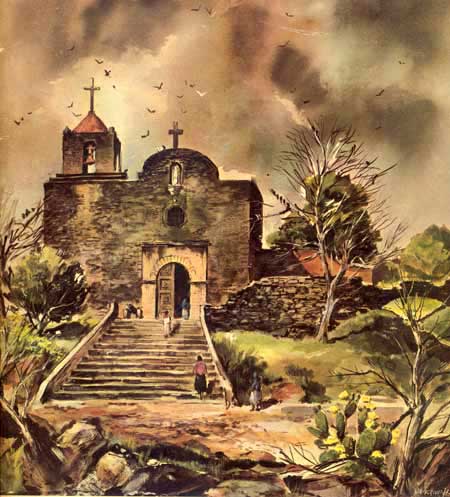

Chapel at La Bahia. Watercolor / 1951 by E. M. “Buck” Schiwetz

March 27, 1836

Mexican soldados murdered Texicans who had defended the garrison at La Bahia. A few managed to escape the massacre by slipping into the underbrush and then into the San Antonio River.

My Irish ancestors (including the grandfather of Lucy Cecelia Fagan) were rescued just before the massacre by a fellow rancher from the old San Antonio River Road — Carlos de la Garza. The story, depending on the telling, had several unusual twists, but the resulting conclusion was always that Nicholas and John Fagan made it to safety due to the intervention of their friend.

Thank you, Carlos, wherever you are.

It’s been 176 years since the Mexicans scaled the walls of the Alamo in San Antonio, bringing death to about 186 Defenders.

It’s been 176 years since the Mexicans scaled the walls of the Alamo in San Antonio, bringing death to about 186 Defenders.

On this early morning in Georgia, I am remembering the Alamo story, as I do every year. It’s a story that I love hearing — that I cherish every detail of. Each year on February 23 (day one of the 13 day siege), I commence some commemorative reading about the event. This year, I chose Gary Zaboly’s “An Altar for their Sons“, an absorbing collection of items published roughly during the period of the Texas Revolution.

Rising early, I like to have coffee in the pre-dawn, listening for the sounds of Santa Anna’s soldiers approaching the walls.

This evening, a quiet dinner will bring a close to this thoughtful day. A steaming bowl of chile con carne, made with buffalo and lots of ancho peppers — that seems appropriate. With a slab of cornbread spread with comino butter laced with tequila and lime.

Along with this bottle of Mission San Antonio De Valero Cabernet Sauvignon.

by Lucy

on August 21, 2011

Place: Rhea Cemetery | Dewey County | Oklahoma

Place: Rhea Cemetery | Dewey County | Oklahoma

A tiny nest of quail eggs in the grass. These chicks will hatch and be nurtured beside my great-granny’s grave in this old cemetery, with only the tombstones to guard them from hawks and other prey.

by Lucy

on February 14, 2011

Recently, I was working on my family history sites GoogleMap where I mark home sites, cemeteries, migration trails and other venues of interest that help tell the story of my ancestors. It’s wonderful that many photos are now tied to GoogleMap locations, so we can get a visual of the areas!

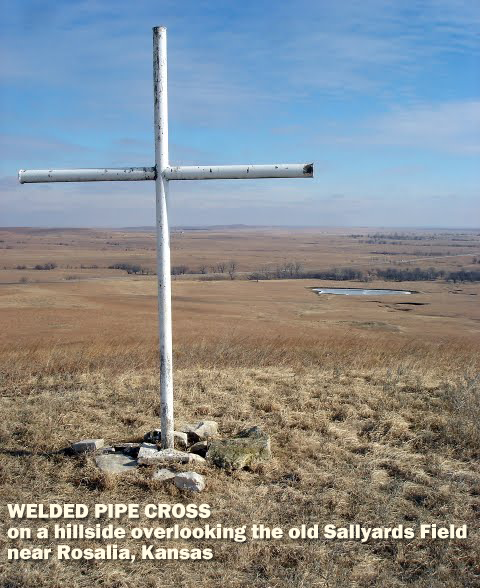

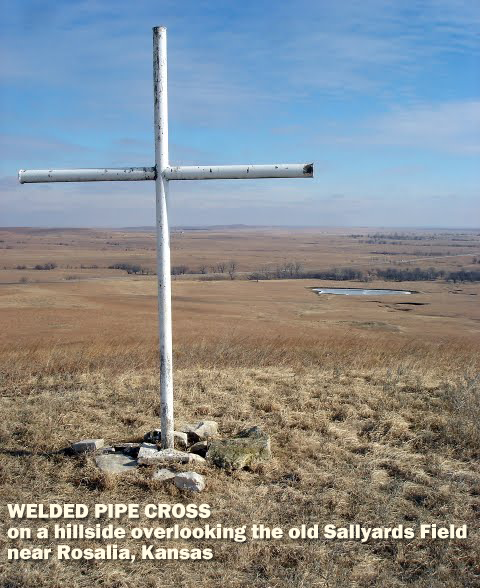

I was particularly trying to accurately mark the location of the old Sallyards Ranch in Greenwood County, Kansas — it became known as Sallyards Field when oil was discovered there in the 1930s. According to online geological records, the area below this hill (up to the tree line by the pond) was the oil field.

What makes this photograph so poignant to me is the story of my grandfather, Dow Caldwell (29 Sep 1899 in Hammon, Custer County, OK – 27 Mar 1934 in Sallyards Field, Greenwood County, KS). He was an oil field worker employed by Skelly Oil Company. After a long day of work, Dow and some co-workers were letting off steam by racing two trucks (loaded with about nine tons of pipe each) up this hill. I know it was up this hill, because the newspaper articles mention that they were racing up a hill — and this is the only hill in this part of the country.) My grandfather jumped from the running board of one truck to the running board of the winning truck to distract the driver from the race. However, his boots were muddy and he slipped. He fell beneath the wheels and the truck rolled over him, ending his life.

My grandmother, Sylvia Caldwell, was about 33 years old when she was widowed. My father was only age 12 when he lost his own father.

In 1994, I journeyed to Kansas to find the grave and death place of the man whose name I share. An old Marine in a diner in Rosalia told me how to find Sallyards. I was there in spring and this hillside was thickly covered with wild blue Verbena. I picked an armful of the lovely flowers and took them with me back to Eldorado, Kansas to the cemetery where Dow Caldwell is buried.

The hillside and flatlands by the pond are covered with deep ruts left by oil field equipment. It’s very quiet now, although relics strewn in the bluestem prairie grass bear witness to it’s ‘heyday’. The cross was not there when I visited those many years ago. Perhaps the cross was welded from some oil field pipes.

I wonder who put the cross on this hill where my grandfather died.

Thank you, whoever you are.

by Lucy

on October 17, 2010

This lonely building, once a busy bank, is one of a very few left in Lehigh, Oklahoma. It is now a quiet country township of wooded lots, country lanes, and simple homes.

Lehigh is in Choctaw Nation, and at one time it was a thriving coal mining community, which may account for this large bank building. My Choctaw great-great granny, Cynthia Jane Hoggard Rogers, was living here with her daughter when she died in 1923.

My research shows that on February 23, 1912, there was a terrible mining disaster in this town.

FLAMES RAVAGE OKLAHOMA MINE

BETWEEN 20 AND 40 BELIEVED TO BE ENTOMBED

SIX BODIES ARE RECOVERED

ONE HUNDRED MEN WALK OR ARE CARRIED TO SAFETY BY RESCUE SQUAD, SOME UNCONSCIOUS, HOPE FOR THOSE REMAINING IN SHAFT IS ABANDONED

Lehigh, Okla., Feb. 23, 1912 — It is believed that between 20 and 40 miners employed in the coal mine of the Wichita Coal and Mining company lost their lives when fire broke out in mine No. 5, entombing the men. The filling up of the shafts with smoke and the failure of the machinery to work prevented their rescue…

Source: Evening Tribune Marysville Ohio 1912-02-23

It’s been 176 years since the Mexicans scaled the walls of the Alamo in San Antonio, bringing death to about 186 Defenders.

It’s been 176 years since the Mexicans scaled the walls of the Alamo in San Antonio, bringing death to about 186 Defenders. Place: Rhea Cemetery | Dewey County | Oklahoma

Place: Rhea Cemetery | Dewey County | Oklahoma